Viking 'sunstone' more than a myth

Ancient tales of Norse mariners using mysterious sunstones to navigate the ocean when clouds obscured the Sun and stars are more than just legend, according to a study published Wednesday.

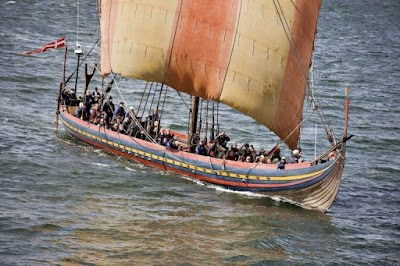

Over 1,000 years ago, before the invention of the compass, Vikings ventured thousands of kilometres from home toward Iceland and Greenland, and most likely as far as North America, centuries ahead of Christopher Columbus.

Evidence show that these fearless and fearsome seamen navigated by reading the position of the Sun and stars, and through an intimate knowledge of landmarks, currents and waves.

But how they could voyage long distances across seas at northern latitudes often socked in by light-obscuring fog and clouds has remained an enigma.

Enter the sunstone.

While experts have long argued that Vikings knew how to use blocks of light-fracturing crystal to locate the Sun through dense clouds, archeologists have never found hard proof, and doubts remained as to exactly what kind of material it might be.

An international team of researchers led by Guy Ropars of the University of Rennes in Brittany, marshalling experimental and theoretical evidence, says they have the answer.

Vikings, they argue, used transparent calcite crystal -- also known as Iceland spar -- to fix the true bearing of the Sun, to within a single degree of accuracy.

This naturally occurring stone has the capacity to "depolarise" light, filtering and fracturing it along different axes, the researchers explained.

Here's how it works: If you put a dot on top of the crystal and look through it from below, two dots will appear.

"Then you rotate the crystal until the two points have exactly the same intensity or darkness. At that angle, the upward-facing surface indicates the direction of the Sun," Ropars explained by phone.

"A precision of a few degrees can be reached even under dark twilight conditions.... Vikings would have been able to determine with precision the direction of the hidden Sun."

The human eye, he added, has a fine-tuned capacity to distinguish between shades of contrast, and thus is able to see when the two spots are truly identical.

The recent discovery of an Iceland spar aboard an Elizabethan ship sunk in 1592 -- tested by the researchers -- bolsters the theory that ancient mariners were aware of the crystal's potential as an aid to navigation.

Even in the era of the compass, crews might have kept such stone on hand as a backup, the study speculates.

"We have verified ... that even only one of the cannons excavated from the ship is able to perturb a magnetic compass orientation by 90 degrees," the researchers wrote.

"So, to avoid navigation errors when the Sun is hidden, the use of an optical compass could be crucial even at this epoch, more than four centuries after the Viking time."

The study appeared in Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical and Physical Sciences, a peer-reviewed journal published by Britain's de facto academy of science, the Royal Society.

Author: Laurent Banguet | Source: AFP [November 02, 2011]

Over 1,000 years ago, before the invention of the compass, Vikings ventured thousands of kilometres from home toward Iceland and Greenland, and most likely as far as North America, centuries ahead of Christopher Columbus.

Evidence show that these fearless and fearsome seamen navigated by reading the position of the Sun and stars, and through an intimate knowledge of landmarks, currents and waves.

But how they could voyage long distances across seas at northern latitudes often socked in by light-obscuring fog and clouds has remained an enigma.

Enter the sunstone.

While experts have long argued that Vikings knew how to use blocks of light-fracturing crystal to locate the Sun through dense clouds, archeologists have never found hard proof, and doubts remained as to exactly what kind of material it might be.

An international team of researchers led by Guy Ropars of the University of Rennes in Brittany, marshalling experimental and theoretical evidence, says they have the answer.

Vikings, they argue, used transparent calcite crystal -- also known as Iceland spar -- to fix the true bearing of the Sun, to within a single degree of accuracy.

This naturally occurring stone has the capacity to "depolarise" light, filtering and fracturing it along different axes, the researchers explained.

Here's how it works: If you put a dot on top of the crystal and look through it from below, two dots will appear.

"Then you rotate the crystal until the two points have exactly the same intensity or darkness. At that angle, the upward-facing surface indicates the direction of the Sun," Ropars explained by phone.

"A precision of a few degrees can be reached even under dark twilight conditions.... Vikings would have been able to determine with precision the direction of the hidden Sun."

The human eye, he added, has a fine-tuned capacity to distinguish between shades of contrast, and thus is able to see when the two spots are truly identical.

The recent discovery of an Iceland spar aboard an Elizabethan ship sunk in 1592 -- tested by the researchers -- bolsters the theory that ancient mariners were aware of the crystal's potential as an aid to navigation.

Even in the era of the compass, crews might have kept such stone on hand as a backup, the study speculates.

"We have verified ... that even only one of the cannons excavated from the ship is able to perturb a magnetic compass orientation by 90 degrees," the researchers wrote.

"So, to avoid navigation errors when the Sun is hidden, the use of an optical compass could be crucial even at this epoch, more than four centuries after the Viking time."

The study appeared in Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical and Physical Sciences, a peer-reviewed journal published by Britain's de facto academy of science, the Royal Society.

Author: Laurent Banguet | Source: AFP [November 02, 2011]